What’s Next for Bishop Strickland?

National Catholic Register, 16 November 2023

This sad tale of the Texas bishop is one of partisanship threatening communion, social-media extremism and new rules for the removal of bishops.

The removal of Bishop Joseph Strickland as bishop of Tyler, Texas, is a story for our time; it could not have been imagined even 10 years ago. It is a tale of partisanship threatening communion, social-media extremism and new rules for the removal of bishops.

The removal of a bishop from his diocese is a sad outcome, even if thought best for the common good of the local Church. In this case, the one person who may not be sad is Bishop Strickland himself. He seemed to desire precisely this outcome. It’s not just that he refused a papal request to resign — and was therefore relieved of office.

In recent months, Bishop Strickland became increasingly extreme in his attacks on the Holy Father, recently speaking at a conference in Rome where he sympathetically read an anonymous “letter from a friend” in which the very legitimacy of the “usurper” Pope Francis was questioned. A bishop who does that as frictions with Rome grow is not waiting to be shown the door, but opening it himself, asking for it to be slammed upon him. It is plausible that Bishop Strickland, now relieved of the pastoral care of Tyler, will be more free to travel and say whatever he wants about the Holy Father.

The Diocese of Twitter

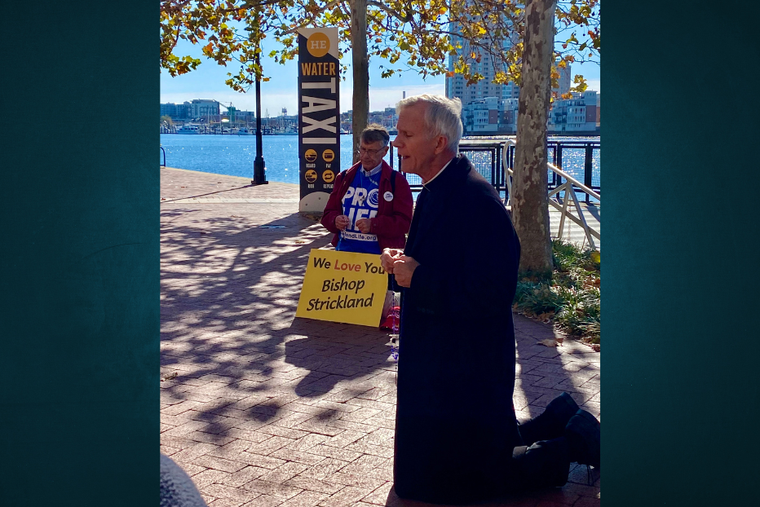

With no offense to the faithful Catholics of Tyler, the diocese is ecclesiastically rather obscure. But Bishop Strickland was not only bishop of Tyler; he was titular bishop of Twitter, where he had more followers than Catholics in his small diocese.

The diocese of Twitter — and analogous internet dioceses — is a rather different thing. The imperative is not to build up the unity of an existing flock, but rather to attract a self-selected flock by sharpening divisions with others.

By all accounts, Bishop Strickland is a rather mild-mannered man. Yet after employing his crozier to bang out tweets, Bishop Strickland became increasingly shrill, no longer promoting communion rooted in the truths of the Catholic faith but styling himself a defender of truth in an aggressively partisan manner. I doubt the bishop of Tyler would ever write a pastoral letter calling the Holy Father a “diabolically disoriented clown,” but the bishop of Twitter did retweet, with approval, someone who did just that.

The bishop of Tyler would not judge it helpful to the holiness of his people to disparage the Holy Father and tear away at the bonds of communion with him. The bishop of Twitter finds it his preferred style of preaching.

Bishop Strickland has now been freed, should he wish to do so, to devote his energies to his adopted, self-selected, virtual flock. The digital world makes that an option now, and Bishop Strickland is not the only cleric who has chosen that path. And he is not the only one for whom it is has ended badly.

Rare, But Less So

Many news accounts of Bishop Strickland’s removal styled it as a “rare” move. That is true. If memory serves, St. John Paul II removed only one or two bishops in his long reign.

Pope Benedict removed four bishops during his pontificate, sometimes without publishing the reasons, as was the case in the removal of Bishop Strickland. The practice thus became less rare under Benedict XVI; namely, the removal of a bishop not for personal misconduct or commission of a canonical crime, but rather for poor governance, maladministration or some circumstance that made continuing in office “not feasible” — as Cardinal Daniel DiNardo of Galveston-Houston said about Bishop Strickland’s case.

Early in his pontificate (2014), Pope Francis updated Vatican norms clarifying that he could “ask a bishop to present his resignation from pastoral office, after having made known the reasons for the request and listening carefully to the reasons, in fraternal dialogue.”

Those “reasons” and “dialogue” do not have to be public. The usual instrument for that process is a confidential “apostolic visitation,” in which the pope sends other bishops to investigate the state of affairs in a particular diocese, usually by means of interviews and a review of documents. A visitation of Bishop Strickland’s diocese was held last June.

Continue reading at the National Catholic Register.